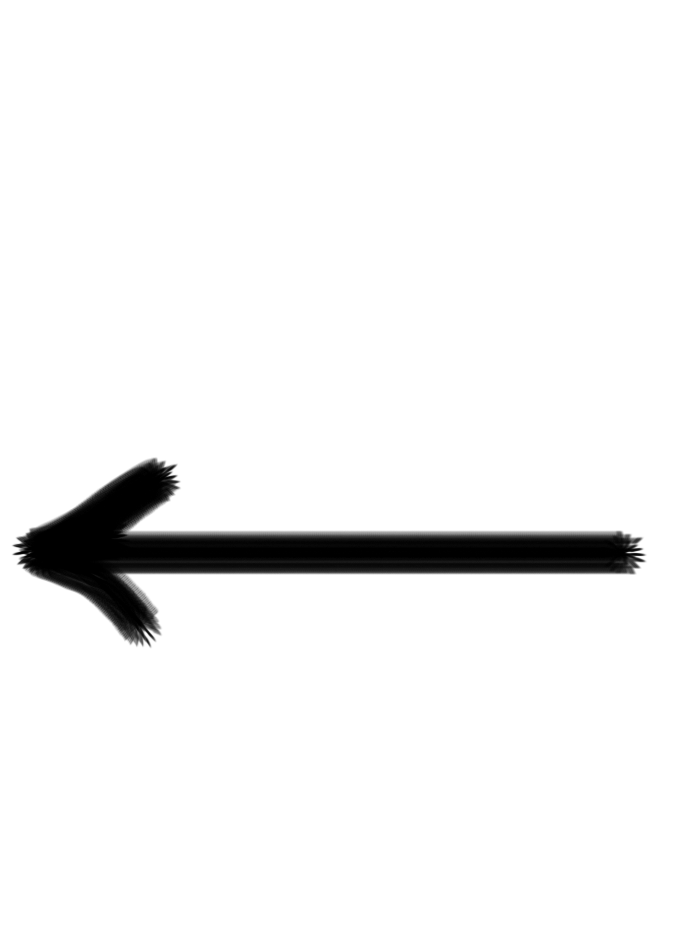

Nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains is Rappahannock County, Virginia. Just a two hour drive from Washington, DC, this rural community of 7,400 sits along an imaginary border dividing rural America from the more densely populated suburban and urban communities of the eastern seashore.

Rappahannock County was named after the Rappahannock, one of many indigenous American tribes conquered during the creation of the colony of Virginia. In 1749 a teenage George Washington surveyed the county seat, America’s first town to adopt the president’s name as its own. During British colonial rule the county’s land was distributed among landed gentry by Lord Fairfax. African slaves built the colonial estates and worked in the orchards that still dot the rural hillsides today.

Along the mountainous western edge of Rappahannock, hardworking Scotch and Irish immigrants settled the rocky hollows of what is today the Shenandoah National Park. For more than two hundred years the descendants of these settlers lived in semi-autonomous communities, hunting in the surrounding forests, farming the hollows, and working in the orchards of the colonial estates in the lowlands to the east.

During the Civil War, Rappahannock and the broader Piedmont Region was staunchly Confederate though the county’s location made it an important thoroughfare for both Confederate and Union troops. In 1900 the United Daughters of the Confederacy commissioned the construction of the Confederate Monument on the grounds of the county courthouse in Washington, Virginia. Today many county residents still fly the Stars and Bars on their properties with pride.

While Rappahannock’s economy was not built around the large plantations that dominated other parts of the South, African slave labor was an important economic motor. In 1840 more than 40% of the county’s population was of African descent, most of whom lived in bondage. Since emancipation much of this population has left the county. Jim Crow laws and a lack of jobs caused many to migrate to Washington DC, Pennsylvania, and Baltimore. Today Rappahannock is more than 90% white. There are no memorials to the county’s victims of slavery.

In 1926 the Shenandoah National Park was authorized by federal and state authorities. A large swath of Rappahannock’s western edge was appropriated for the park. Hundreds of families were pushed off their land and resettled in the county’s lowlands. Wounds from the park’s creation still run deep for the descendants of displaced families. It is often expressed in mistrust of the federal government and the national political establishment.

Rappahannock’s rolling hills, beautiful views and proximity to Washington, DC, make it a popular tourism destination. Since the 1980’s professionals and retirees from Washington and New York have been moving to Rappahannock. This influx of outsiders has increased county tax revenue and has steadily improved land values. However, the county’s median income has not grown with the same speed and many working families once again feel they are being pushed out. The county ranks 64th (out of 3,084 jurisdictions) in the nation for “income inequality”. The agricultural economy that sustained the region is gradually being replaced by rural tourism and other service industries. Simultaneously progressive social trends popular in more urban areas are challenging the traditional values that once defined the region.

In 1980 my grandparents, Linda Remington Dietel and William Dietel, moved to Rappahannock County. They fell in love with this rural corner of America. My grandmother started a small sheep farm and my grandfather commuted to New York city via Dulles International Airport. Many of my childhood holidays were spent on the farm. I explored the nearby forests pretending to be on adventure filled frontier expeditions and in the pastures I fought imaginary Civil War battles.

For 37 years my grandparents have happily called Rappahannock County home. Prejudiced by my “Yankee” upbringing, this seemed strange. Understanding why this is and beginning to grapple with my own implicit biases have been my motivation for doing this exhibit. Today, I have come to call Rappahannock home.

Rays of the late afternoon sun stream through a hollow along the edge of the Shenandoah National Park. In 2016 more than 1.4 million people visited the Shenandoah making it the 5th most visited National Park east of the Mississippi River. However, the region wasn’t always a destination for hikers and campers. Hundreds of small communities used to dot the hollows that now make up much of the park. Residents of these communities were displaced by the park’s creation and forced to resettle in the lowlands of Rappahannock and adjoining counties. As a result resentment for the Federal Government and its politicians still runs deep in many Rappahannock families.

Stewart Settle fastens a shaft on a workbench at Settle’s Garage in Flint Hill, Virginia. The garage is owned by Stewart’s older cousin “Bubby”, and is an important community space for the residents of Rappahannock County. The Settle family was one of many families forced out of the mountains during the creation of the Shenandoah National Park.

The “Lunch Bunch” have their men-only lunch at the Public House, a restaurant in Flint Hill, Virginia. The daily gathering is attended by local businessmen, retired Washington lawyers and political insiders who now call Rappahannock home. Just four days before the 2016 presidential election, the focus of a lively debate was the Trump campaign and the potential consequences of a Trump victory.

A home on Sunnyside Road in Washington, Virginia.

Matt Pflausen catches his breath after helping load a herd of cattle into his cousin Mike Peterson’s trailer. After leaving the restaurant industry Mike started Heritage Hollow Farm with his wife Molly. They specialize in producing quality grassfed beef and lamb. While the county’s agriculture is still dominated by larger landowners using traditional farming methods, there is a growing community of young farmers interested in community supported agriculture market models and sustainable sustainable agriculture methodology. The proximity of Washington DC’s metropolitan economy and local niche market of rural tourism has allowed many of these operations to grow. However the expensiveness of land hamstrings all agriculture in the county, and many younger farmers worry about the long-term sustainability of agriculture in Rappahannock.

The overgrown office of a defunct mill sits abandoned off Lee Highway. The highway was named after the Confederate general Robert E. Lee. Today in Rappahannock county there are few old mills remaining, and none in commercial operation. However, Lee Highway remains an important route for rural tourists traveling to the Shenandoah National Park.

A woman watches her child ride a merry-go-round at a carnival in Front Royal, Virginia. While not in Rappahannock County, Front Royal is an important economic hub for the surrounding region and the largest nearby town for many Rappahannock residents. Front Royal’s Avtex factory used to employ thousands until it was closed by the Environmental Protection Agency, due to repeated pollution of the regional watershed. The plant’s closure hit the local economy hard, leaving many families struggling to make ends meet.